Time-Dilation Attacks on the Lightning Network

by Gleb Naumenko and Antoine Riard on May 20, 2020

We explored applying Bitcoin’s peer-to-peer layer attacks against the Lightning Network to steal funds from payment channels.

Time-dilation attacks currently seem to be the most practical way to steal funds via an Eclipse attack for several reasons. Neither hashrate access is required nor the attacks are targeted at merchants only.

Here’s the full paper.

- Intro

- Why is this important?

- Is it just a theoretical concern?

- But can’t the victim just see that no blocks arrive?

- The attacks

- Okay, how to actually fix it?

- Conclusions

Intro

Protocols on top of the Bitcoin base layer are really cool. They offer tremendous opportunities in terms of scalability, confidentiality, and functionality, at a cost of new security assumptions.

We all know payment channels have to be monitored, otherwise, the funds can be stolen. That sounds too abstract though. We decided to study what an attacker actually has to do to steal funds from LN users.

More specifically, we explored how peer-to-peer layer attacks can help with breaking the assumption above. Per time-dilation attacks, an attacker controls the victim’s access to the Bitcoin network (hard, but not impossible) and delays block delivery to the victim. After that, the attacker exploits that the victim can’t access recent blocks in a timely manner. In some cases, it is enough to isolate the victim only for two hours.

Then the attacker makes a couple (totally legit) actions on the Lightning Network towards the victim’s channels, and at the same time commits a different state instead. Since the victim is behind in terms of the latest blockchain tip, they cannot detect this and react as required by the protocol. We demonstrate three different ways the attacker can steal funds from the victim, and discuss the feasibility/cost of these attacks. We also explore the broad scope of countermeasures, which may significantly increase the attack cost.

In short, the takeaways from our work are:

- Many Lightning users (those with Bitcoin light clients) are currently vulnerable to Eclipse attacks.

- Those Lightning users which run Bitcoin Core full nodes are more robust to Eclipse attacks, but the attacks are still possible as the recent research suggests.

- Eclipse attacks enable stealing funds via time-dilation.

- Time-dilation attacks can’t be mitigated with just observing slow block arrival, so there is no simple solution to (3).

- Thus, time-dilation is a practical way to steal funds from eclipsed users. Neither it requires hashrate nor targeted at merchants only. Light client users are a good target because they are easy to attack. Full node users are a good target because they are often used by major hubs (or service providers), and stealing their aggregate liquidity might justify the high attack cost.

- Strong anti-Eclipse measures is the key solution. WatchTowers are cool too.

Why is this important?

First of all, time-dilation attacks are feasible against a lot of LN clients today. At the same time, these issues are fundamental and won’t go away. We’ll somewhat cover this more in the next sections.

This work, however, should not be considered as a criticism of LN. Instead, the goal is to make the LN security model more clear. Broadly speaking, understanding these issues and mitigations would help to make the platform more mature. When Lightning gets broader attention, thousands of participants will have to consider these attacks when making sure their stack is secure.

Our work can become a motivation for the following:

- for Bitcoin and Lightning protocol developers to work on the related protocol improvements and countermeasures.

- for lightning integrators (e.g. Lightning Service Providers) to do things right (deploy the countermeasures and use best practices).

- for lightning users to make an informed decision about the software they use.

- for other protocols on top of Bitcoin to be secure.

- for all of us to bring more attention to security issues of not-so-core parts of the Lightning stack (e.g., light clients).

Is it just a theoretical concern?

An attacker neither has to control key infrastructure (e.g., the victim’s ISP) nor rent any hash rate. An attacker can steal from multiple channels at once (even belonging to different victims) to justify the cost of the attack. A victim doesn’t have to be a merchant.

To steal funds with time-dilation, an attacker should open a channel with a victim and eclipse (isolate) the victim’s Bitcoin client. The former is usually doable: LN nodes often accept requests for opening a channel by default.

The latter, Eclipse attacks, are generally considered to be very difficult.

Eclipse is as far as an attacker can get without physical access to the node.

According to the latest research, they are practical against Bitcoin Core full nodes only if an attacker has access to the critical Internet infrastructure. Attacking just Bitcoin software (for example, AddrMan poisoning) alone is believed to be insufficient. However, if the gain from an attack is high, an attacker may justify the high attack cost by stealing full available victim’s capacity (or even from several victims at once). This is a reasonable assumption about the LN hubs or service providers, which often run (as they should) full nodes.

As for the light clients, eclipsing them is unfortunately not that difficult at all. There are very few Bitcoin nodes that can serve light clients, and light clients have poor anti-Sybil mechanisms. Same with Electrum. Thus, it requires an attacker to run a couple of hundreds of malicious nodes/servers with distinct IPs to Eclipse light clients. To be clear, it can be done from scratch within an hour for less than 100$.

But this is true assuming light clients connect to random Bitcoin nodes from the network. If light clients are connected to the user’s own Bitcoin node (via Neutrino or Electrum), that is perfectly fine. Bitcoin Core nodes can still be subject to the attacks, but the issue is not as severe.

Light clients can also be connected to trusted nodes. For example, a wallet app may have a Bitcoin light client talking to the wallet developers’ full node in the background. Lightning is supposed to be non-custodial, so we can’t just assume that it’s fine to trust a node of your wallet provider. If the trusted nodes are used along with random nodes, that’s better, but still hard to reason about. To the best of our knowledge, some of the top Lightning wallets use this model.

The problem here is that the software can be correct and properly implement a semi-trusted model (with both trusted and random peers), but the trusted party can still time-dilate the victim’s channels. For example, a wallet developer can scam all their users at once and disappear.

In our work, we focus a trust-minimized scenario (no trusted nodes at all), similarly to the Bitcoin threat model, although most of the time-dilation aspects are agnostic to the victim’s source of blocks (we just assume an Eclipse attack is possible).

But can’t the victim just see that no blocks arrive?

This is not a reliable way to detect time-dilation because mining is a random process. For example, every day there are on average seven 30+ minutes block intervals. That’s why the problem is so hard to mitigate in full.

The only real countermeasure used in Bitcoin Core today is stale tip detection: if a node doesn’t observe a block within the last 30 minutes, it attempts to make a new random connection to someone in the network.

In the paper, we argue that the optimal attack strategy is to maintain a window of 29.5 minutes before feeding a new block to the victim. In this case, an attack can fail only if one of the blocks naturally took way too long (at least 30 minutes). The probability of failure is around 6%.

Failure case means the victim might have a chance (but not guaranteed) to break free from eclipsing. Note that this measure is not implemented in Neutrino, so an attacker can just stop feeding blocks at all, and exploit the time dilation earlier than against Bitcoin Core.

Improving this kind of detection, because it would be either gameable or would have a very high false-positive rate due to naturally “slow” blocks. An honest user can’t distinguish a “slow” block from being under attack, so they can only make a good guess. These solutions are also problematic because even stale tip detection has already way too high false-positive rate (seven times a day) despite being not very effective against time dilations.

Other solutions based on detection are not that simple either. For example, looking at the timestamps in a block header is tricky, and the exact analysis to be applied is not clear.

But even if the detection worked, what a victim would do? The reaction boils down to anti-Eclipse measures, which should be implemented in the first place, without any triggering. That’s why we emphasize that fighting Eclipse attacks is the key solution to time-dilation attacks.

The attacks

First of all, the attacker should eclipse the victim’s Bitcoin client from the honest network. Then the attacker has to find the victim’s Lightning node and open a channel with the victim. The attacker can also start with an open channel and then find and Eclipse the victim’s Bitcoin client, it doesn’t matter.

After that, the attacker has to perform time-dilation: they start delivering blocks to the victim at a slower rate, up until the victim is N blocks behind the actual tip, where N is defined by the particular configuration (usually hours to days).

In the case of Bitcoin Core, the time-dilation speed is limited by 20 minutes delay per block, due to the implemented “stale tip detection”. For Neutrino, an attacker can simply stop feeding blocks to the victim. That’s why it would take longer to attack Bitcoin Core in the descriptions below.

In our descriptions, the estimated attack timings are based on the most optimal time-dilation strategy suggested in the paper. In terms of the amounts, all three attacks may result in stealing full channel capacities, according to the current implementations.

Now let’s describe three ways to steal the funds from payment channels of time-dilated Lightning nodes.

Targeting Channel State Finalization is similar to a regular Bitcoin double-spend: the attacker pretends they agree to update channel state and receives something, but then closes the channel with a different value. Since the victim can’t see the latest tip, they won’t transmit a revocation transaction. The default safety block delta currently implemented is at least 144 blocks, so the attacker would have to eclipse a victim for at least 24 hours (36 hours if Bitcoin Core is used).

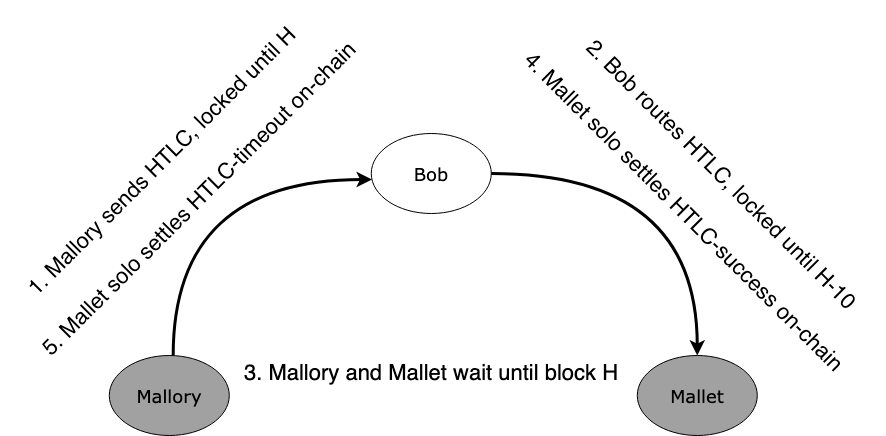

Targeting Per-Hop Packet Delay is based on routing via the victim, and the victim should have at least two channels with the attacker.

Similar to the first attack, it will be too late for the victim to react when they finally reach the actual blockchain tip. Per this attack, the default values are around 14-144 blocks depending on the implementation, so the attacker has to keep the victim eclipsed for 2-24 hours (4-36 hours if Bitcoin Core is used).

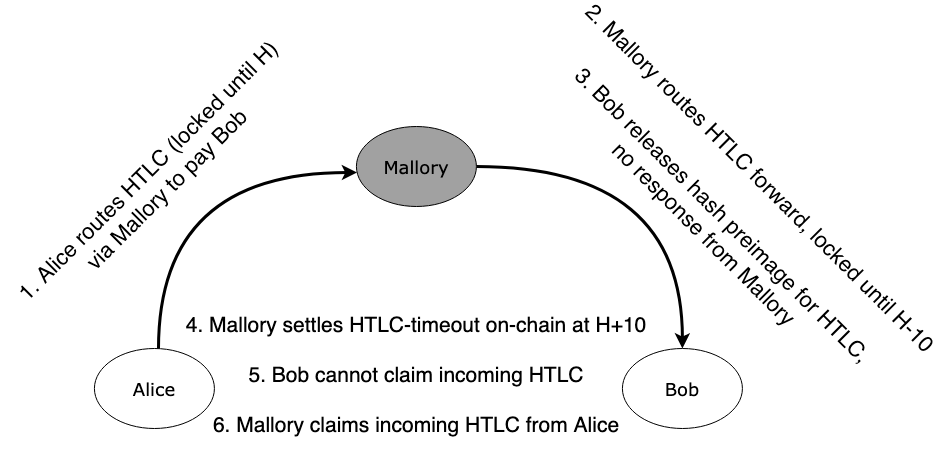

Targeting Packet Finalization is the most creative approach, and the most feasible too! The attacker just does not responds to the victim, when the victim sends them a preimage for the incoming HTLC.

The relevant safety policy states 7-11 blocks in this case, so the attacker has to keep the victim eclipsed only for up to 2 hours (3 hours if Bitcoin Core is used).

Okay, how to actually fix it?

First of all, WatchTowers are great (e.g. The Eye of Satoshi), they should help to keep an eye on your channels and act if someone attacks you.

But it’s sort of cheating from the protocol perspective: it’s effectively one more trust assumption. A user becomes bonded with the WatchTower provider. Some designs suggest accountable WatchTowers, but again, that’s new assumptions and should be explored in detail. But after all, they can be attacked too, or even bribed!

We’ll see how WatchTowers work out in practice, but let’s think about the solutions without new assumptions.

Most of the “non-cheating” countermeasures are about redundant ways of accessing the Bitcoin network. The more creative the better! Blockstream Satellite, or relay block headers via Lightning. One can also run their own WatchTower under some redundant infrastructure (luckily, the software is usually open-source).

P2P-layer privacy improvements help too. No, Dandelion probably won’t work (you’re welcome to try though), and Tor is tricky too. But there is hope with other ideas. Maybe we’ll see some mixnets (based on Lightning?) or SCION architecture in the future.

In case you are wondering why we don’t talk about detection-based solutions, please get back to this section and read more in the paper. They may be helpful too, but they are not sufficient.

Conclusions

We believe that Lightning is super cool and it is already an important part of the Bitcoin stack. It is going to get more attention in the future, so the security model should be well-understood, especially since it’s different from what Bitcoin has. Time-dilation is an example of that: it is an LN-specific class of attacks, although in practice it requires Bitcoin’s peer-to-peer layer exploitation.

Our work explores time-dilation attacks in detail and suggests how to minimize the damage. We encourage all protocol developers (especially those working on light clients) to pay attention to anti-Sybil and anti-Eclipse measures.

We hope our work will help to make the Lightning Network more mature and motivate participants of the system to use best security practices. We covered some cool parts of the paper ideas here, but there’s much more there, please read.

Bonus: Open Problems

Exploring time-dilation attacks spawned a bunch of discussions between the two of us, and we wanted to share some of them with those who managed to find this section. These are different from the Discussion section in the paper because they are less related to the time-dilation attacks.

We would be happy to learn if any of these ideas were already discussed or are in works!

- We are interested in exploring the liquidity/security tradeoff of payment channels, especially in light of the attacks. We believe that not only the channel capacity should define the CSV/CLTV timelock values. A particular user’s security (e.g., whether a WatchTower is used) should be taken into account too.

- We are also interested in exploring new mechanisms of post-unilateral agreement. It should be possible for Bob to fallback to the fast cooperative close even if a unilateral close was initiated by him due to Alice’s irresponsiveness.

- In future, we may see a cohort of malicious miners causing a cascade of channel closings and fee bumpings if Lightning Nodes use stale tip detection to force close channels. We are interested in seeing whether this may be profitable for miners, especially in light of the low block subsidies. We already mentioned this question in a mailing list earlier this year.

- Instead of eclipsing the victim’s Bitcoin node, an attacker can eclipse a Lightning Node to control which channel announcements the victim receives. It would be interesting to explore whether an attacker can manipulate the victim’s routing to harvest fees or spy on the victim’s payments via this approach.

If you are interested in exploring any of these or have something similar in mind, feel free to reach out.